An Iranian visitor can’t help but notice the Zoroastrian symbols that dominate old Mumbai.

In the historic Fort District toward the southern end of this metropolis of twenty million souls, Zoroastrian monuments take center place at intersections and crossroads, while small signs warning “Entrance for Parsi Irani Zoroastrians Only” pop up here and there, hinting at discrete entrances to the many fire temples hidden in the neighborhood.

Article by Alex Shams, ajammc.com

![DSC_2659-1024x685 DSC_2659-1024x685]()

There are somewhere between 60-100,000 Zoroastrians living across the Subcontinent, with the vast majority concentrated in Mumbai. A similarly vibrant (if much smaller) community of a few thousand live in Pakistan’s Karachi as well.

Within the Zoroastrian community of the Subcontinent, there are internal divisions, primarily between Parsis — who trace their roots to a group of Zoroastrians who arrived from Iran in the 10th century fleeing persecution — and the Iranis, who arrived in the 19th century. The boundaries between the communities are sometimes blurred, a process furthered by the sporadic arrival of individual Zoroastrians from Iran to India outside of those two waves. All members of the faithful, however, share a belief in the creator Ahura Mazda and the Prophet Zoroaster, in line with the religion’s teachings developed around 3,500 years ago.

In Iran — where Zoroastrian was the state religion until the arrival of Islam — the holy winged Faravahar symbol of the ancient Persian monotheistic faith has been transformed in the last few decades into a kitschy emblem of Persian ethnic pride. A symptom of the symbol’s commercialization is that the most common place it can be found is probably at cheap jewelry shops, where they sit amid big crosses (popularized by the Latin music wave of the 1990s) and trinkets shaped like marijuana leaves.

![DSC_2660-1024x685 DSC_2660-1024x685]()

The Zoroastrian community in Iran numbers around 25,000, and fire temples and other holy places can be found in most major cities across the central Iranian plateau. But the community is so spread out that outside of Yazd it is difficult to pinpoint any specifically Zoroastrian neighborhoods. Indeed, while Zoroastrianism in Iran is extremely visible as a symbol of an ‘ageless’ Iranian national pride, Zoroastrians as living individuals are hardly acknowledged.

In Mumbai, the position of Zoroastrians is quite different, with concentrated communities and a highly noticeable, concentrated physical presence in the urban fabric. Although Zoroastrians in India proudly announce and cherish their roots in Iran, their historical prominence and relative economic success as a community makes them hyper-visible in this cosmopolitan entrepot. Here is a city where every religious, linguistic, cultural, and ethnic community in India is represented, and the Zoroastrians’ long-time residence and success in the area has assured them a prominent place in the urban hierarchy.

For many Zoroastrians, Iran is a kind of legendary homeland, a place that they believe they were unfairly driven from but whose culture and history they are somehow connected to. Material connections to contemporary Iran in the community are surprisingly common.

The pages of the Mumbai community’s newspaper Parsi Times, for example, contain advertisements for heritage tours of Iran, including but not limited to Zoroastrian sites. Bohman Kohinoor, the 92-year-old owner of one of the most famous of the few dozen Parsi eateries left in the city — Britannia and Co. — was born in Iran and even returned for his honeymoon.

In both Mumbai and Karachi, the two main cities in the Subcontinent where Zoroastrian communities reside today, the impact of the Zoroastrian community can be strongly felt across the urban fabric. Distinctly Zoroastrian neighborhoods have emerged and are legitimated through the erection of public monuments and temples that materialize the community’s claim to belonging in the urban and national fabric. In some neighborhoods, the Faravahar sits on multiple temples, fountains and shops on the same block, creating the impression of Zoroastrian “space” even though the neighborhoods count only a handful of actual Zoroastrian residents.

![1503927_10103063913419775_5605016718740054055_n 1503927_10103063913419775_5605016718740054055_n]()

The interior of Britannia and Co. restaurant.

Mumbai’s neighborhoods are an elaborate patchwork of varying religious traditions, and Hindu, Jain, and Sikh temples, mosques, ashurkhanehs, churches, synagogues and a wide variety of other religious monuments project a specific religious community’s belonging on a certain street or neighborhood. This demarcation of space is related to the fact that Karachi and Mumbai serve parallel roles, as both are the largest city and greatest magnet for domestic migration in their respective contexts.

As a result, their urban fabric is covered by districts hosting migrants from every region of the country, and the presence of a community neighborhood in the city signals to a certain extent their legitimate place among the nationalities, regions, religions, and ethnicities of the nation.

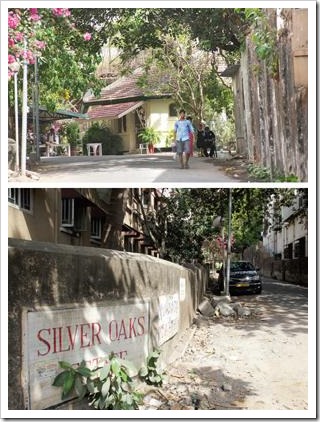

In both cities, long-established and wealthy “Parsi Colony” neighborhoods sit proudly among the host of districts named for communities that cover their respective city maps, in addition to the variety of Zoroastrian symbols that dot other neighborhoods as well.

A religious diversity poster at the Mahalaxmi Temple near Haji Ali Dargah in Mumbai. Unfortunately, Zoroastrianism was forgotten by the well-intentioned creator.

No matter the successes and visibility of Zoroastrian communities across the Indian Subcontinent, however, the community is still a tiny minority in a sea of more than 1.7 billion people. Their visibility in the urban fabric masks the very central fear of “extinction” that in many ways defines internal discourse in the community.

![DSC_2642-1024x685 DSC_2642-1024x685]()

An ever-present subject among Zoroastrians is the decline in community numbers, a product of low rates of marriage and birth as well as high rates of emigration to the UK and other Western countries. In India, the clerical elite refuses to consider children born of mothers from outside the community as Zoroastrian (although in Pakistan the situation has recently changed), a factor which has left community numbers dropping quickly. The situation even led the Indian Ministry of Minority Affairs to launch a (quite embarrassing) campaign called Jiyo Parsi to encourage young Zoroastrians to get hitched and stop using condoms, leading some to angrily respond that Parsis “are not Pandas.”

![DSC_2681-1024x685 DSC_2681-1024x685]()

One ad associated with the campaign in particular highlights the ironies of the community’s fear of a slow, quiet extinction. Among the campaign’s many patronizing and at times brazenly sexist ads, one takes aim in particular at the historical visibility of the community in the urban fabric by attempting to stoke fears that “Parsi Colony” will turn into “Hindu Colony” if the next generation doesn’t start procreating soon. Indeed, today in India — and in Mumbai specifically — the Parsi legacy is most felt in its visible prominence in the public sphere.

Interestingly, the prominence of this Iranian-descended community contrasts sharply with the near invisibility of Iranian and Persianate culture more broadly in the Subcontinent today, which since 1948 has been subsumed into Indian and Pakistani national culture. While Zoroastrians today appear to be an almost out-of-place minority group, the community was historically part and parcel of a wider elite Persianate subset of Indian identity. For centuries in India, the Persian language was the language of the courts and the arts, and Persian customs and style were markers of high breeding before the British institutionalized control in the second half of the 1800s.

![DSC_2555-1024x685 DSC_2555-1024x685]()

Indeed, it is difficult to understate the historical impact and influence of Persian on the elite culture of the Indian subcontinent, despite the almost complete erasure of this dimension of Indian history from the public imagination. The language maintained such an extensive literature that the dialect used locally even developed its own standard, called Indo-Persian, and both Mumbai and Calcutta were centers for Persian-language publishing well into the 20th century. Even if most Parsis arrived in the 10th century before Persian became well-established, by the 1500s they found themselves living an environment the broader Indian ethos of the moment had turned deeply Persianate.

As contemporary fears of the disappearance of the Parsi community show, however, that period has long passed, and in an age of increasingly monolithic and homogeneous state nationalisms, Zoroastrians are but one of many small, formerly elite communities in India that are slowly disintegrating. The Arab Jewish Baghdadi communities that once dominated commerce across British India (including modern-day Myanmar), for example, have almost disappeared completely into Israel, while Armenian communities across the Subcontinent have increasingly packed up their bags as well.

One problem is that many elite business communities believed that their interests lied with the British during the colonial period. Baghdadi Jews, for example, largely stopped speaking Arabic over the course of a few generations and switched to English as a home language.

Similarly, Zoroastrians tended to view the British in a positive light, and symbols of affiliation and allegiance to Britain continue to decorate some Parsi restaurants even today.

Mumbai Starbucks emblazoned with the logo of TATA, one of the world’s largest companies that was founded and is still run by local Parsis.

![DSC_2651-1024x685 DSC_2651-1024x685]()

It was no wonder that the rise of the Two-Nation theory — which posited the need for separate states in South Asia for Muslims and Hindus — left Zoroastrians in a complicated place. Bereft of their former British patron and stuck between dueling visions of India that offered these former elites only a marginal position, Zoroastrians could either leave for Britain or face a deeply uncertain future. The 1998 Indian film Earth dramatizes this struggle, depicting a Parsi family in Lahore whose world is turned upside down despite their deepest hope to remain neutral and stay put.

For the most part, however, the community escaped Partition unharmed. But the rise of the right-wing Hindutva ideology across India in recent years — which imagines Muslim and Christian Indians (including millions of followers of the Syriac, Nestorian, and Chaldean rites) as individuals foreign to the national body politic — threatens to go even further, taking the ideology of Partition to its full logical extent and expunging the Subcontinent of a diversity that has long refused to fit into the clearcut boxes of modern nationalist and religio-supremacist ideologies.

Amid this landscape, India’s Parsi and Irani communities occupy a unique if still uncertain place. As a largely wealthy, urban community, they do not fear the growing communal tensions that have been stoked by recent rumors of forced mass conversions of minorities amid the lingering memories of the 2002 riots in Gujarat or the 1984 anti-Sikh pogroms.

Indeed, their fear is of a quiet death on the shady lanes of Mumbai’s Dadar Parsi Colony, of a day when the fire temples will fall empty and museums will be set up in their place. Regardless of what happens, however, the memory of this small diasporic Iranian community will live on in the urban fabric itself. The fear among Zoroastrians, however, is that they may end up increasingly like their Iranian counterparts: remembered fondly instead of lived with happily.

All photos courtesy of the author.

The post Parsi Mumbai: The Legacy of Zoroastrianism in India’s Urban Fabric appeared on Parsi Khabar.

![]()

When he is not fixing his patients’ teeth, he is penning Urdu couplets. But orthodontist Dr Navroze Kotwal’s passion for Urdu poetry, especially its sublime form ghazal, has been a source of pique for his friends. “You are a Parsi, right? How come you speak Urdu so well and do shairi,” ask his friends. “Is it crime for a Parsi to learn Urdu and write poetry in it,” quips Dr Kotwal gently.

When he is not fixing his patients’ teeth, he is penning Urdu couplets. But orthodontist Dr Navroze Kotwal’s passion for Urdu poetry, especially its sublime form ghazal, has been a source of pique for his friends. “You are a Parsi, right? How come you speak Urdu so well and do shairi,” ask his friends. “Is it crime for a Parsi to learn Urdu and write poetry in it,” quips Dr Kotwal gently.