![]()

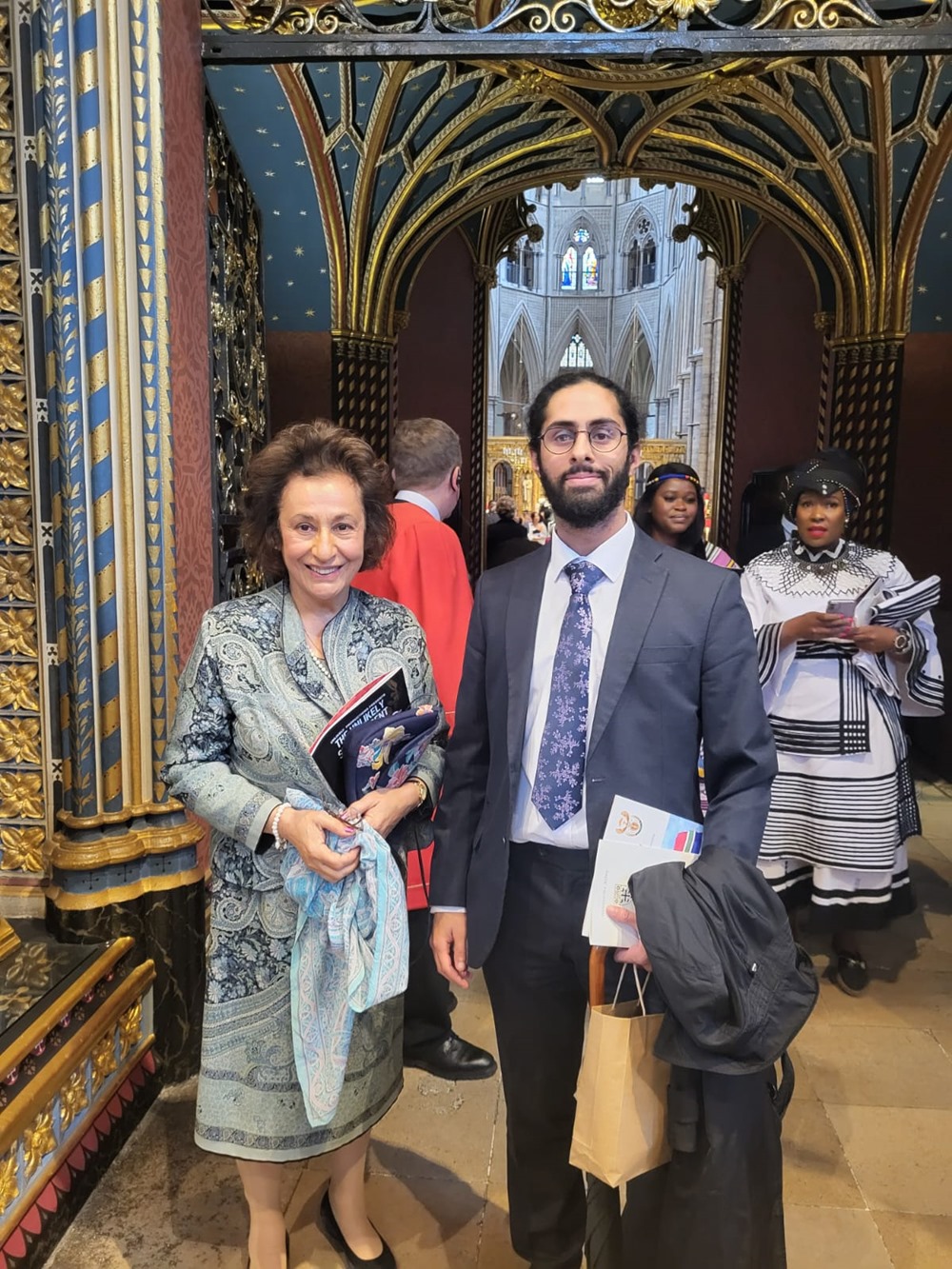

Iona Italia talks to Nev March about her historical novel, Murder in Old Bombay, and about the Zoroastrians of Bombay both past and present.

Hello everyone, welcome to the Quillette podcast.

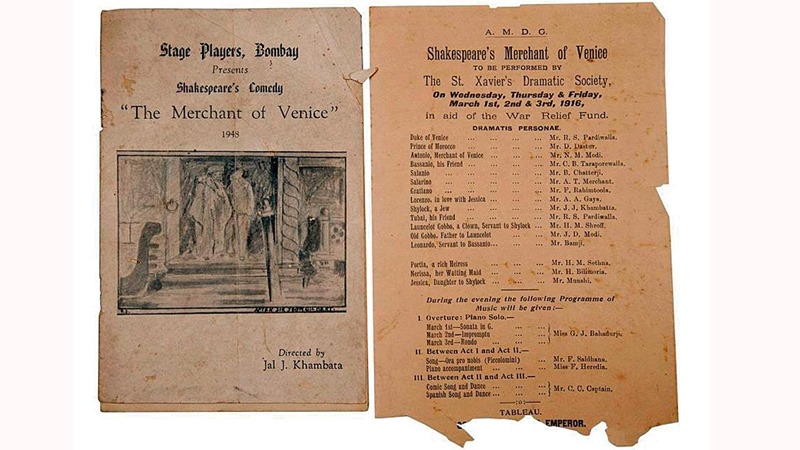

I’m your host this week, Iona Italia, and my guest is Nev March. Nev is a former business analyst turned novelist. Her debut novel, Murder in Old Bombay, was published in 2020, and it’s the first in a series of mysteries featuring the detective James (Jim) Agnihotri. There are two sequels already out: Peril at the Exposition (2022) and The Spanish Diplomat’s Secret (2023).

![clip_image002 clip_image002]()

![clip_image004 clip_image004]()

And I believe you’re currently writing book four. Is book four out yet?

Nev March: No, not yet and it won’t be out for a year—but it is almost done. This month, it will be turned into the publisher.

Iona Italia: Wow, that’s exciting. Each of the novels has a slightly different setting and they are all centred on historical mysteries that you have revisited.

Nev teaches creative writing at Rutgers Osher Institute, and she is, like me, a Parsi Zoroastrian. That topic is going to come up later in our conversation. We’re going to talk today about the first book, Murder in Old Bombay, which features an unsolved historical mystery that took place, which affected the Parsi community. I think we’ll begin with Nev reading a little bit from the beginning of the book, which will set the scene for that. Then let’s talk about the historical events and what is known about them and what first drew you to that story. Welcome, Nev.

NM: I’d be delighted to. Thank you. OK, here goes.

THE WIDOWER’S LETTER

(POONA, FEBRUARY 1892)

I turned thirty in hospital, in a quiet, carbolic scented ward, with little to read but newspapers. Recuperating from my injuries, a slow and tedious business, I’d developed an obsession with a recent story: all of India was shocked by the deaths of two young women who fell from the university clock tower in broad daylight.

The more I read about it, the more this matter puzzled me: two well-to-do young women plunged to their deaths in the heart of Bombay, a bustling city under the much-touted British law and order? Some called it suicide, but there seemed to be more to it. Most suicides die alone. These ladies hadn’t. Not exactly. Three men had just been tried for their murder. I wondered, what the hell happened?

Major Stephen Smith of the Fourteenth Light Cavalry Regiment entered the ward, empty but for me, ambling as one accustomed to horseback. Taking off his white pith helmet, he mopped his forehead. It was warm in Poona this February.

I said, “Hullo, Stephen.”

He paused, brightened and handed me a package tied in string. “Happy birthday, Jim. How d’you feel?”

The presents I’d received in my life I could count on one hand. Waving him to the bedside chair, I peeled the brown paper back and grinned at the book. Stephen had heard me talk often enough about my hero.

“The Sign of the Four—Sherlock Holmes!”

He nodded at the newspapers piled about my bed. “Interested in the case?”

“Mm. Seen this?” I tapped the Chronicle of India I’d scoured these past hours. “Trial of the Century, they called it. Blighters were acquitted.”

Outside, palm trees swished with a warm tropical gust. He sat, his khaki uniform stark in the whitewashed ward, smoothing a finger over his blond moustache. “Been in the news for weeks. Court returned a verdict of suicide.”

I scoffed, “Suicide, bollocks!”

Smith frowned. “Hm? Why ever not?”

“The details don’t line up. They didn’t fall from the clock tower at the same time but minutes apart. If they’d planned to die together, wouldn’t they have leapt from the clock tower together? And look here—the husband of one of the victims wrote to the editor.”

I folded the newspaper to the letter and handed it over. It read:

Sir, what you proposed in yesterday’s editorial is impossible. Neither my wife Bacha nor my sister Pilloo had any reason to commit suicide. They had simply everything to live for.

Were you to meet Bacha, you could not mistake her vibrant joie de vivre. She left each person she met with more than they had before. No sir, this was not a woman prone to melancholia, as you suggest, but an intensely dutiful and fun-loving beauty, kind in her attention to all she met, generous in her care of elders, and admired by many friends.

Sir, I beg you do not besmirch the memory of my dear wife and sister with foolish rumours. Their loss has taken the life from our family, the joy from our lives. Leave us in peace. They are gone but I remain,

sincerely,

Adi Framji (February 10th, 1892)

II: Thank you so much. So, tell us a bit about the Rajabai Clock Tower deaths. I believe this happened in 1891.

NM: It did indeed, yeah. And it is pretty much as I described. I used a lot of the details from the original case. For example, the two women did leave home in the afternoon and climbed to the top of the Rajabai Tower. It was open to the public at that time. It was fairly new. And first one and then the other fell to her death around four o’clock in the afternoon when there were people around. It shocked the university, I imagine.

But there were a lot of missing details that didn’t make sense. For example, one of them, Bacha, her glasses were missing. This is in the original case. And Parsis wear this sacred thread around our waists. For some reason, they were not able to locate that. And then her pallu … The women of that time wore a scarf tight around their head, tucked behind the ears, so that the sari could be pinned to it. Her pallu was missing as well in the original case, I remember. And there were a few other things like that that just did not make sense for suicides.

Of course, the case was never really solved. And it became such a zoo. There were newspapers that took one side and the other. There was actually a trial. And some of the newspapers defended one of the accused, who was himself a Parsi boy, a young man. So, it was really chaos. Then there were false accusations. The police inspector was accused. He was considered to have taken a bribe, and it turned out to be all nonsense.

There’s just so much that went wrong with that case that it really did change the way policing happened. The police force was actually restructured in the decade after this case. So, it was fairly pivotal.

II: It took place in broad daylight, right? People saw them fall: first one woman and then the other. And it involved the Godrej family who are a well-to-do Bombay Parsi family. When I lived in Bombay, I walked by the Rajabai Clock Tower. It was quite close to where I lived in South Bombay, which is the historical centre of Bombay. I lived in Cushrow Baug in the Parsi community, on Colaba Causeway, kitty corner across from Leopold’s Cafe.

NM: I know it well.

II: If anyone is familiar with Gregory Roberts’ epic novel Shantaram [2003], large parts of that novel took place in the Leopold and I read large parts of that novel at the Leopold. And the Godrej family, I assume, is the same family who now own Godrej Nature’s Basket, which is a swanky [supermarket chain].

NM: And many other things, yeah. Many other things. I was very impressed with the original founder of the Godrej Enterprises, Ardesha Framji, the original one. He did not remarry after his bride of one year passed away, so all the descendants are from his siblings. But he was a serial entrepreneur and created a number of businesses. He was also something of a patriot because he really believed that India could produce goods, rather than just buying them from Manchester and England, and he founded a lot of the businesses that now turned into industries in India. He’s a fascinating person, because all this happened when he was 22 years old. And I had this feeling that someone that is so intelligent and so forward-thinking would not rest easy and would hire a detective and find out what actually happened to his wife, even if he never made it public. So, this was pure supposition on my side, but it led me down this path to discover what had happened or what could have happened to the girls.

II: What attracted you to this period in history? So, this is pre-Independence India. I think the independence movement was just getting started. Gandhi was in South Africa at this time, right?

NM: Yes, so Gandhi went to South Africa in 1893 and he stayed for almost 20 years. So, he was nowhere in the picture. But the independence movement had started in a fashion. I mean, you had people like Alan Hume, who were British, telling the students in Calcutta that if you want to be treated as adults, essentially, then you need to step up and consider patriotism and not your own purse. “Be men, not children,” is what he told them. But you had Gokhale, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who was a moderate, who was mustering certain Hindu support. And then you had Tilak, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who was a radical, an extreme orthodox Hindu. And he actually was one of the folks that mustered public support for nationalism. It wouldn’t really take off for another 20 years until Gandhi came back. But he ended up being fairly divisive in terms of communal harmony.

The first intercommunal riots between Hindus and Muslims took place in 1893 in Bombay and 1894 in Pune. And they took place because of a very sad reason. There used to be a Muharram procession, which is a holy month for Muslims. And in those days, a bier, like a coffin, of the various saints would proceed in procession throughout the entire city. Hindus and Muslims all participated in it. It was a very joint endeavour. And then after Tilak joined and became vocal about the protection of cows, because Muslims eat beef, and he opposed that, that procession then split into two, with the Muslims carrying on the Muharram procession and those traditions, and the Hindus creating their own Ganesh processions almost at the same time. It’s a recipe for disaster. You have two processions in two different directions that are likely to collide. This was a situation ripe for intercommunal disharmony at that time. And since that time, it has only gotten worse. In the last 30 years since I left India, I am so disheartened by the decrease in secularism and the rise of militant Hinduism. It’s breaking my heart that the India I loved that was so secular, that was a shelter to all religions is a shadow of itself today.

II: Yeah, it’s a totalitarian ideology, the new-found Hindu nationalism, very different from the inclusive nationalism that was starting at the time of the novel in the 1880s and 90s.

Dadabhai Naoroji, who was the first Indian in the British Parliament … the first two Indians to be Members of Parliament in the UK were both Parsis and they were also involved in the beginnings of that independence movement. At this time, I think the main demand was for Indians to be allowed to serve in the British Civil Service in India, which was entirely manned by Brits.

NM: By Englishmen. You’re right, Iona, even though technically in 1863 or some such year Indians were allowed, you have to remember that they had to pass the exam by the age of 22—maybe it was 23—and later that became 19, not having an English education. Most Indians came to an English education late in their teens because all the elementary work would have been done in a regional language.

They suffered tremendously not having the classics, not having that rigorous, Eton education. They could not compete at the age of 19. So, it was functionally prohibited, if not by the letter of the law. You do have a gentleman, a Tagore actually, the older brother of the famous Rabindranath, who did join the civil service. In 1896, he retired from the Maharashtra High Court. He was a judge in the Maharashtra High Court, not in Bombay per se, but outside in one of the courts there, Satara District, if I’m not mistaken. You know, when you do this research, the strangest little details stick in your head. I love this stuff. I know you can tell.

II: Yeah.

NM: I love this stuff because the era is so filled with change. If we think today that we have a lot of change going on … in my lifetime, the internet, computers, social media have taken off. So, in the last 50 years, enormous change. These poor guys who were living at the turn of the century had far more change than us: transportation, how you ate, gasoline, electricity, phones, cars, everything happened in those couple of decades around the turn of the century. It interests me to see how people process this, the difficulties that they handled. The time is filled with conflict: the old versus the new, the women’s progression of establishing our own identities and separation a little bit from the duties of family. Of course, that would take many, many more decades. But even getting the vote… So much change happened in those couple of decades, give or take, that are around the turn of the century.

That era does fascinate me. In a way, it’s a time of innocence, but the blinkers are falling off. It’s delightful to see. It’s also a little painful to see because you have Parsis who are literally Anglophiles. We enjoyed great patronage under the British and admired the honesty, integrity, the rule of law, the upstanding nature of the national character. But then, as you just mentioned, a lot of Parsis started getting involved in the national movement and realising that India as a whole was suffering, was under so many pressures: not just taxes—exorbitant taxes that would leave people destitute—but also the numbers of influenza and cholera and dengue and the bubonic plague, the number of deaths just skyrocketed in those early years: 1910, 1920, 1930. And I think a lot of Parsis then realized that social justice was just so far out of reach if you did not have self -government.

II: Yeah. I want to return to the Parsis and also give people more specific background there. But first, I wanted to talk about Jim. The main character, he is Anglo-Indian. Initially, the term Anglo-Indian, in the mid 19th century, if I understand right, was usually used to refer to British people who had grown up in India. But later it came to mean people who are half Indian, half British. His mother was an Indian woman who had fallen into disgrace, but she was originally from a high caste, Brahmin caste, as we can tell from his surname, Agnihotri. And his father, whose identity remains unknown for most of the novel, was British and probably an army officer. Jim himself was in the Indian army.

How many Anglo-Indians were there in the army at that time? Can you say a bit about the different ways in which these mixed -race children were treated at that time? Were there differences between the way girls were treated versus boys and differences between cases where the mother was British and the father Indian and vice versa?

NM: There are almost no cases where an Indian man had children with a British woman. This is the reason for clubability, right? The clubs kept the white community to itself, so that the British women would only socialize with British men. White men did not want the mixing of the races. That’s true of both sides. Indians did not want races to mix either. In fact, they did not want castes to mix. So, within the strict Indian society, there were taboos, divisions between the four major castes and multiple sub-castes. There’s almost no caste that is equal. It’s an entire hierarchy. There’s always somebody that you’re better than, always somebody that you’re worse than. Social status had much to do with it, but it’s also wealth. Some communities were wealthier and so on.

So how did this happen? In the 1700s, and perhaps even the late 1600s, you did have British men marrying or having Indian women as their housekeepers and wives. They would never have imagined taking them back to England with them, but they would probably spend the rest of their lives in India. By the 1800s, it was considered “going native” and frowned on. You would lose your job if it was found out, as a British civil servant or as an employee. Going native was considered very, very bad. So, they ended up wearing these heavy woollen clothes, even in the hot tropical summers, just to maintain their separateness.

But you did have English men having relationships with Indian women as concubines, as mistresses. And they would have children, but those children were rarely owned. Now it does happen that occasionally those Englishmen would claim the child as their own. And some of those have become army generals. You can see the portraits: they’ve clearly got an Indian cast to their face, but they have a British name, and they had a British education. It was very, very rare for that to happen, because it came with a huge amount of social stigma, both for the parent as well as for the child. So, very often, they were discarded.

Kim, the book by Rudyard Kipling, is an English boy who is raised as an Indian. But more often, the Anglo-Indian children were pariahs. They were cast off. Sometimes missions—like I described a mission in Pune [in the novel]—would take them on and essentially turn them into priests, give them jobs, or keep them within the fold, give them a living in some fashion. But in terms of the society, the Anglo-Indians frequently tried to fit in with the Brits and were on the periphery, hangers-on, grateful for a kind word. Many of them turned to the hotel industry. So, you had a lot of them as managers, because they spoke English well. So, you had them clustering in certain areas, like Goa. The original Portuguese area had a lot of trade, and so you had some amount of that. There are stories of entire little towns that were created by the Brits for the Anglo-Indians, like, “You guys stay to yourselves.” Again, more segregation than mixing. It was, in those days, I think, a sad thing to be an Anglo-Indian, because you were neither fish nor fowl, you were neither Indian nor were you really British.

But in later years, when I was growing up, for example, my neighbours were three sisters who I loved dearly and Anglo-Indian and had beautiful grey eyes and therefore, everyone admired them. They were almost foreign—foreign being a very positive thing to be in those days—and charming girls, and they did very well. So, by the 1960s and 70s, it had become, if not a positive thing, at least an accepted thing. Many Anglo-Indians left during the independence time. There were many that migrated to Australia. Engelbert Humperdinck, for example, is a wonderful singer. He left and went to the UK and became very famous after that.

Many Anglo-Indians hid the fact that they had a half-Indian side and did fairly well in America and the UK passing for white because if you could, there was more privilege to doing that. And in a sense, I think they felt that exclusion all along, so it was natural that they would want to leave during the enormous tumult of independence. But many stayed, and therefore there’s a warm community of mostly Catholic, but some Anglican communities within India, in the south—in Bombay certainly, but Pune had a good number and Goa I know has a lot.

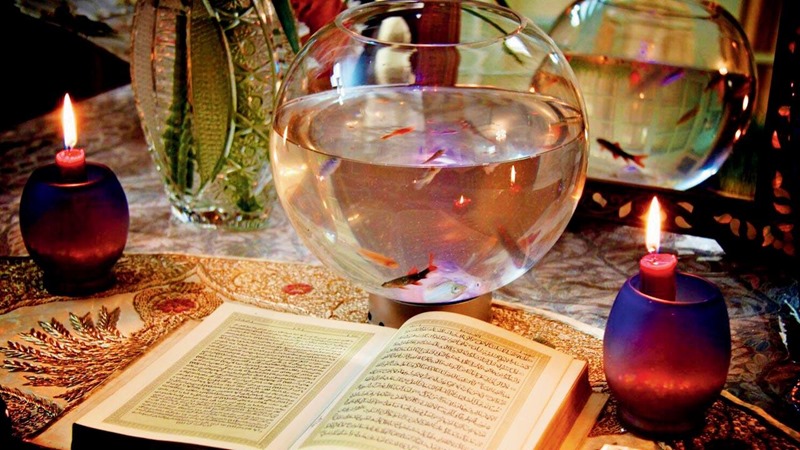

II: Thanks. Yeah. So … just to talk about the Parsis a little bit before I read a passage from the book—the same one that I read last time [when Iona interviewed Nev for Areo Magazine’s Two for Tea podcast]—which is, I think, the very heart of the book is the question of Jim’s integration or non-integration into this Parsi family, his ability to marry a Parsi woman. I just want to give people who have no idea what the Parsis are—because it’s not universally known—a little bit of background. The Parsis were originally from Persia and legend has it that a small group of Zoroastrians from Persia came across the sea to Gujarat. They landed in Sanjan in Gujarat during Mohammed’s lifetime. This was in the eighth century, when Persia was Islamised by the sword. I since read that archaeological digs have shown that there was actually already a trading Parsi community in Gujarat previous to that, so in fact, they’d been there for even longer. I think that’s now backed up with DNA evidence. I have talked about Indian and Parsi DNA to the geneticist, Razib Khan. He’s fallen foul of the Hindu nationalists because he was part of a group who were able to show that the caste system in India has been very, very strictly adhered to for over two millennia. It wasn’t an introduction of the British. We can see by tracing the DNA record that different castes have not been interbreeding with each other almost at all for 2,000 years. So, the Parsis arrived around the seventh or eighth century, a really long time ago—longer than the Maoris have been in New Zealand, to give some context—and brought their religion of Zoroastrianism. I think the most well-known aspect of that religion is the sky burials, the traditional form of burial, which is being placed in a Tower of Silence. The ones in Bombay are like giant upside-down colanders, with three concentric rings of slots. The men are placed on the outer ring, the women inside and any dead children in the inner ring. Traditionally the bodies are eaten by vultures. Nowadays, they also have to use solar panels to try to desiccate the flesh. There are unfortunately very few vultures left in India today. But the flesh is eaten by vultures and the bones fall down into a heap. And it’s those heaps of bones in a characteristic pattern that showed archaeologists how long the Parsis have been in India, probably as trading communities along the Gujarat coast.

It’s a very small community and in some ways historically has been very liberal and forward-looking. Parsis were the first to educate women. But, in other ways, very conservative and, in particular, Parsi identity is very ferociously policed, especially in India. The identity is officially patrilineal, and I mostly find that people accepted me, even though my mother was not Parsi, only my father. My father was born in Bombay. He was actually 21 on Indian independence. (My parents were quite old.) So, my father was born in the Raj, which is really extraordinary, and went to Pakistan in the 60s where he worked for Tata. I spent the early years of my life in Bath Island, Karachi in the Parsi baugh there, which no longer exists, I believe, or is almost completely dissolved. I was mostly accepted as a Parsi by people in India, but there were a few strict people who didn’t want to accept me, even though I have had navjote initiation and my father was Parsi, et cetera. There are many people who don’t accept you if your father was not Parsi, so if your mother was Parsi, but your father was not, or if you were a Parsi woman who married a non-Parsi, or if you are the step- or adoptive child of a Parsi couple, or the husband or wife. The religion doesn’t accept converts and there is identity politics on steroids, a ferocious attempt to preserve a sort of blood lineage. I’ll let you talk.

NM: Yeah, all of that is true in India, absolutely. I have to tell you; the West has left some of those patterns behind. In North America, I think we’re at least 20, 25,000 people now and we are much more inclusive. We welcome the children of whoever, if it’s the man or the woman. The spouses are welcome. Most of them don’t convert, but they are welcome in the communities.

II: Yeah, thank goodness.

NM: There are groups where conversion is active. In California, there are 700,800 converts. They’re coming back to the religion of their grandfathers and great-grandfathers, essentially. And for many of them, it feels like a homecoming. Ethnically, these are Iranians who look like us. So, they feel welcome, and they have a lot of the actual equipment, like the sudra and the symbolism, all the objects that you have for devotion, they even have them in their houses from that long ago. So, for many of them, it’s a homecoming. But for some new converts, it is a choice. A couple that I know that have taken turns as the president of ZAMWI (the Zoroastrian Association Metropolitan DC area). And both husband and the wife were born of another religion. The wife came from a Lutheran background, the husband from a Muslim background. When they got married, they decided to both choose another religion so that they could belong to something that was neither his nor hers. They looked at the Baha’i religion and a few others, and they chose to become Zoroastrian. The woman and actually taught the Avestan class. That’s so impressive to me because you have to really know the stuff to be able to teach it. And Zareer is a paediatric oncologist, God bless him. That has to be one of the hardest jobs in the world to be a paediatric oncologist and that’s what he does. So, this is not your run of the mill couple. You can tell I admire them tremendously. They chose to be committed to the community. And I think that’s really what it is: it’s community. We’ve realized that whatever’s worked for the Zoroastrians in India in preserving identity, in preserving culture—and we admire them for it—there has been a price to pay for that. And that if we continue to follow that path, we are essentially discarding almost one half of the population. That’s why the numbers are so ridiculously low. We have an 18 percent decline every decade. To be shrinking at almost 20 percent in a decade is the death knell for any community.

But if you include the women, we are either staying stagnant in numbers or growing. So hey, guys, let’s include the women—even if you don’t believe it’s the right thing to do, just for the numbers. This is my liberal spiel that I profess. And it just feels so much more natural in today’s day and age where you have women leaders. Our president of ZAGNI [the Zoroastrian Association of Greater New York] is a woman. The vice president, me, I’m a woman. We have so many women in leadership positions. Why should our children be disadvantaged just because we happen to be of the female gender? It just feels so unfair. So yeah, there is a clear movement towards more inclusion and fairness. And in India, I have to tell you, they may get to it kicking and screaming because there is a proposal for a uniform Civil Code in 2026. Muslim women are jumping up and down for joy. And the Parsi community, which is still very much ruled by men, is opposing it tooth and nail. So, I have a feeling that they will come to progress kicking and screaming, but they will come to it.

II: You mentioned Avestan by the way: that’s a dead language, ancient Persian, in which the Zoroastrian scriptures are written. Actually, the lady that I lived with in Bombay was also an Avestan teacher and scholar. She did the translation of Zoroastrian scriptures, which I have here my bookshelf. She did a parallel text version, which has English, Gujarati and Avestan. Yeah, that’s her. She’s in her early 90s now and still teaching, giving her Avestan classes.

NM: Oh, I have that book, I have it, it’s wonderful, yes!

II: She’s still living in the flat where she was born in Cushrow Baug, which is where I stayed when I lived in Bombay for a couple of years.

NM: Maybe we should describe the baughs, just because Bombay is a teeming city of 20 million—and that’s from a decade ago, that number. There have been thousands coming in every day on the train from villages everywhere. So, Bombay, Mumbai is bursting at the seams. And then in this city of skyscrapers that is just Manhattan on steroids, essentially, you do have enclaves called the baughs. These are little residential properties that the Wadia charities or the Bombay Parsi Panchayat purchased and set up, where you have trees and wide roads and playgrounds and temples and these gymkhana spaces where people hang around in their cotton singlets and chat and play carom and play table tennis and boys play cricket and the girls play badminton. These are little pockets in the middle of a bustling city that are frozen in time. They have these 100-year-old trees, and they still have that wonderful ambiance.

II: Yeah, the one where I stayed is Cushrow Baug, which is probably the nicest of the ones in Bombay. It has big, imposing gates at the front. And we have attendants at the gate. The gates haven’t been closed, though, since the terrorist attacks of 2001. [That] was the last time, I believe, the Cushrow Baug gates were actually locked. But there are people there who will ask you what your business is if they don’t recognize you and who you are coming to see. It’s very much like going inside an Oxford or Cambridge college. It’s got that feel. It’s a series of courtyards with low-rise, three- to four-storey flats. I think they were built probably at the end of the 19th century. There’s a lot of art deco architecture down in the historic part of South Bombay. They have a slightly art deco feel. There are big green spaces in between each of the courtyards. And this is right on Colaba Causeway, set back a little bit from the street, but in probably the busiest, most chaotic, craziest part of Bombay city. And we had a football court, a cricket pitch. There’s a pavilion where the old people would sit outside playing bridge and playing chess, with a canteen and with a fire temple also. And there was also a guy who would come round wheeling a tray and he would go round to all of the flats at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. And you could go out and buy your food from him, and also somebody who would come around to get your washing and to do your ironing and things. So, an extraordinary little patch. Like going into the quads for Americans. I think Cornell is the closest thing that I saw to Cushrow Baug in the United States. Yeah, very much like an old-fashioned college. I live here in Sydney and the reference here would be the Sydney Uni main quad that kind of feel or like going into a boarding school. That is the feeling architecturally. It’s pretty quiet in there—for Bombay, I should qualify that—and there are also a number of these scattered around in Bombay. My friend Zubin was at the Tata colony, which is not gated, but you could tell when you were entering the colony because suddenly there was no litter on the streets. Up until then, it was a chaos of litter and people selling things and people sitting on the pavement, crowded pavements and a lot of rubbish. Bombay is unfortunately a very deeply smelly city. There are some good smells, but also any gap between two houses is just piled high with absolutely stinking litter. There’s a lot of litter everywhere in the streets. And suddenly, you turned a corner, the streets were clean, it was quiet, and that was the entrance to the Parsi baugh. So, there are these little islands of Parsis living within the city.

Non-Parsis are not permitted to go into the Parsi fire temples, which are actually something quite sparse inside. You’re not missing that much. It’s not that exciting, people. But yeah, non-Parsis are not allowed to go in. And also, there is a well in Bombay, and I think there are a couple elsewhere, a holy well where you’re supposed to go on certain days that are dedicated to water. And there’s also the very large and beautiful park area where the Towers of Silence are, the Doongerwadi, which is also open to Parsis only. And there are people at the gates who, if you don’t look Parsi, will ask. I was only asked once or twice. I was much more Indian looking because I was very tanned when I was in India and my hair had also not started to go grey. So, I had really dark hair and I was wearing sari. So mostly I wasn’t questioned, but a couple of times I was questioned. A couple of my Indian friends who looked Parsi had been to the fire temple. An old boyfriend of mine who always passed for Parsi, he had gone in. Nobody had questioned him. So, the temple has been permanently desecrated.

NM: You know, it’s so funny. There was this statement that some elderly person had made that if your shadow falls on the fire, it will pollute the fire. I said, “Firstly, that is physically impossible for a shadow to fall on light, because shadows fall away from light. And secondly, how do you pollute something like fire or water—what does that even mean?” So sometimes there are myths and stories and taboos created just to exclude. Those are some of the things that we try to rationalize and make sense of in today’s day and age. Does this really matter anymore? There’s a taboo. When I was growing up, those 10 days of the Gathas … Since we have a monthly calendar, we have 10 days that don’t belong to a month. And they’re in between the previous year and the next year. And they’re called Days of the Dead or Days of Prayer, the Gatha Days. And at one time when I was growing up, I went to a Parsi school, and you were not allowed to cut your nails or your hair during that time and it made no sense because if you had a hangnail you were fiddling with it constantly. It was so distracting. You’re not supposed to cut it. My mom told me that when she was growing up you’re not supposed to touch metal—not even pick up a sewing needle or scissors.

Over the centuries, whatever the original intention was [was lost]—make time for prayer by not doing the regular work of cooking and whatnot—so you eat simple meals. You just eat things that are stored, some form of dry cookies. Those rules and traditions turned into taboos. You may not touch iron. And got so exaggerated that we all forgot what they were originally intended to do. One of those traditions is the exclusion of women during the time that we have periods. When I was growing up, my mom was already against it. She was a pretty modern person. But her mother suffered this tremendously. One week of every month, she was banished to an outhouse where there was a thin, hard mattress. She was stuck in there. The food would be brought to the door. She was not allowed to touch anything, because she would pollute it by touching it. How very lonely and demeaning for a young girl—you typically get your period at 11 or 12—to be excluded from the family life like that. That you’re suddenly an unclean object is the closest I can come to that feeling. Luckily that tradition has gone away because people like my mother and even my grandmother realized that’s nonsense. We have soap. By the way, we invented soap. So now we can be clean. We don’t have to worry about blood contaminating everything that the person touches. So, sanity did prevail. Unfortunately, a lot of women did suffer tremendously. I think about generations of women and how low it made them feel. But they sucked it up. They swallowed that because that was the way things were done. And luckily, we have moved on.

II: There are these menstrual taboos in a lot of cultures, especially, South and East Asian cultures. It feels to me like it’s a throwback to some fear of nature, that what you’re trying to do with religion is control life. I’m a little bit influenced by Camille Paglia in this. There’s this archetypal opposition between the divine, the male, the control, the ritualistic. And then there’s nature, which is uncontrollable. Nature fucks you over. Nature is a very double-edged sword because it brings you fertility, but it also kills you. So, there’s this desire to banish and control the things that you don’t have control over as a person. I think that got caught up in that.

NM: I find it interesting that all those traditions usually disadvantage women. Why didn’t they disadvantage boys getting through puberty when they start growing hair, or they have wet dreams, or they start masturbating? Why didn’t those things become the stuff that got tabooed and controlled? Why is it women that every culture has tried to suppress and control? Is it just being physically weaker? Is that the single common denomination of every single culture?

II: I think it’s being physically weaker and also having the power to have children. It’s possible to control women because of physical weakness. And it’s also a mysterious and powerful thing, being able to give birth. So, these are archetypal superstitions: we’re banishing the menstruating woman because blood is frightening and because nature is uncontrollable and sometimes messy, so if we shove that off to one side we can pretend to be completely in control of stuff.

NM: It’s disguised in terms of purity, at least in our religion. At least in religion, because Zoroaster in the Gathas talks about women and men everywhere. Nerebiascha, nerebiascha. He talks about them almost like that. So, there’s a lot of equality in the original teachings of the prophets. But in the community, in the traditions, there is such a lot of disparity. So where does this come from? It comes from a tradition of purity. I have to go back a little bit. In the Middle Ages, if you had surgery to be performed, there is some documented evidence that, in Italy, for example, you would pay a Persian twice as much as you would pay a local surgeon, a physician. The reason was your chances of surviving the surgery were much higher. And why? Because the surgeons were priests, the magi, and they would pass their instruments through the holy fire while saying certain prayers. No matter how fast you blab those prayers, it takes a certain amount of time to say the prayers. And therefore, your instruments get sterilized. I don’t think they realized what they were doing; they were just following the recipe. But a sterile knife cutting through a human body is likely to be better than unsterile equipment. And therefore, this is documented, the purity rituals benefited the community in that fashion. Now, they probably took it to extremes because cleanliness is close to godliness [and] all those ideas. In the 1800s, purity became extremely important. Remember that this is also the time where Hinduism had the untouchables—all the people that did the dirty work, right? Lifting carcasses, cutting meat, cleaning gutters, cleaning toilets, cleaning houses. All the dirty work, all the real manual work was delegated to the Dalits, which is a large portion of the caste system. I would say upwards of maybe 50 percent of them are all one caste, which is untouchable. Therefore, they were suppressed. Hinduism had this tradition that if, in the morning, the first person you saw was a Dalit, your day would go bad. These are people who were traditionally taught to look down, hide themselves, try to appear invisible, sneak around, don’t upset people, because you will get beaten. So, Dalits had been suppressed in Hinduism and why? Under the guise of purity, cleanliness. And I’m sorry to say, Parsis did the same crap. You know, we took on the mantle of purity and men are always pure, but women aren’t always pure. No matter how good a person you are, your body is unclean, so you are unclean. So culturally, we’ve taken on a lot of attitudes from Hindu culture because that was the mainstream culture. We wear a sari, which is, again, not something Persian. We stopped speaking Farsi or Avestan. We started speaking Gujarati, our own horrible version of it, we change the grammar.

II: I love Parsi Gujarati.

NM: People laugh, you know. It’s so not authentic, but we softened all the vowels essentially and we dropped off all the conjugated verbs at the end. So, we have a very different form of Gujarati, which sounds very pleasant to my ear compared to the traditional orthodox Gujarati. That’s because we grew up with it. Anyway, we’ve taken on a lot of good and bad, I’m sorry to say. But that’s what happens when you’re in another culture. There’s a certain osmosis that happens. A lot of our food is based on Indian ingredients and recipes. And we love it.

II: I’m going to read a passage from the novel. This is probably my favourite moment in the novel, and it is slightly revealing the plot, but nothing to do with the main mystery whodunit part of the plot. So, I think it’s okay to reveal this bit.

This is from Murder in Old Bombay. Confrontation.

Burjor, by the way, is the father of the main female character, Diana.

“Have a seat, Captain.” Burjor indicated the settee, and dropped into a chair.

I sat down with growing concern. He’d been a generous host all evening, but now his customary bonhomie was conspicuously absent. Had I given cause for rebuke? Searching my memory brought forth no clues. Had something occurred this very evening?

A long pause followed in which he appeared to consider an opening. However, he did not speak. Instead he rose and went to the alcove by his desk that contained his saint’s portrait. There he bent his head before it and prayed softly.

Remonstrations I could have managed, even an uncalled-for reprimand. His strange expression was … fear? Surely not. Some deep-seated worry, then. My puzzlement melted to compassion for my troubled host.

“Whatever it is, sir. Let’s have it,” I said into the oppressive quiet.

He returned after a few moments, his footsteps unwilling, and slumped on the brocade seat. His deep-set eyes regarded me steadily.

“Sometimes I’m not sure,” he began, “that I’m doing the right thing. It helps, to speak to the prophet.” He motioned toward the alcove, saying, “You know we are Parsees, of course.”

I nodded, further mystified at his choice of topic. He continued, “But you may not know what that is. We are Zoroastrians, followers of that ancient prophet Zarathustra.” Pointing at the saint’s portrait, he went on. “We do not convert anyone to be Zoroastrian. Centuries ago our ancestors came to Gujarat as refugees, from Pars, in Persia. We are very few—perhaps a hundred thousand in all.”

I waited. This history did not explain the ominous tone of his interview.

He said, “So if a son or daughter marries someone who is not Parsee, well, they can no longer continue the race. They are as good as lost to us.”

I offered, “I’ve heard Mrs. Framji speak about it at breakfast.”

“Yes!” His voice lifted in palpable relief. “So you see?”

“Well, no.”

My words drew him back into a fretful state. He rocked in his chair.

“Captain, you cannot marry Diana,” he said, finally.

Whatever I had expected, it was not this. Astonishment gave way to bitterness. I was a mixed breed, a bastard, not worthy of his daughter. Had I not seen that mix of pity and disapproval all my life? Indians did not tolerate the mingling of races any more than the English.

In polite circles, a man who was happy until then to shake my hand would hear my name, James Agnihotri, and pause. His shoulders would stiffen, and he might spot an acquaintance across the room, and need to meet him. Women who seemed perfectly gracious—as they heard my Indian surname, their eyes might widen with understanding. Those quick glances of confirmation, how well I knew them, and the reserve that followed, polite, distant and final.

But this, from Burjor, whom I extolled as an exemplary father! That he thought so little of me cut deep. I wiped emotion from my face, but now he seemed attuned to me and grimaced an apology.

“No, Captain, it’s not that. I see great merit in you. We owe you a great deal! You are not responsible for an accident of birth.”

His chest swelled with a heavy breath. “No, it is Diana. Two brides were lost to us … to my clan, Captain. We cannot lose another!” The creases around his mouth deepened. His voice dropped to a whisper. “Our customs are all we have.”

NM: Oh, well done, Iona. How beautifully you read.

II: Thank you. So, you said before we started recording that you had placed some Easter eggs in the novels about Parsi culture and tradition. And I know our listeners are very interested in this topic. So, tell us more about that.

NM: Absolutely. Each of my novels is based on real history, usually something less known. The last one, for example, The Spanish Diplomat’s Secret, has to do with the genesis of the Spanish–American war over Cuba. But, of course, my characters are immigrants, right? They’re the couple that are Indians. And so, they’re outsiders. They have the outsider perspective, which I find very useful, very valuable, because you can hold up a mirror and show truths that someone from a culture may not really consider, or not even think about, because you’re so used to things. So, every book also has the evolving story of this couple’s relationship. And since she’s Parsi, there are these little hidden details, little Parsi traditions that are buried in there.

I’ll give you an example. When I was very young, I watched my mom and my grandmother perform something called “the book key method.” The book key method is a very old tradition and a way of finding lost valuables. You don’t use this if you misplaced your glasses or your pen or something small. You use it if you misplaced a will or a deed to the house or some valuable document or diamond earrings or something really precious because it takes about an hour to perform the ceremony. It begins and ends with prayers, of course. All our ceremonies begin and end with prayers. But the actual performance of it is fascinating and gave me this creepy feeling, almost like watching a Ouija board. It’s very strange.

So, what you do is you have a holy book, typically the Avesta and into it you put an iron key in such a way that the handle of the key is sticking out of the pages and the teeth of the key are inside the pages. Then you take your prayer string, what we call the kusti, and you bind the whole thing together and tuck the end in. So now it is very firmly fixed and is one object. And then two people sit across from each other, and they hold the book up with their fingertips on either side of the key, the handle of the key that’s sticking out. So, the whole heavy book is now dangling in the middle. And this is why it takes so long: you have to empty your mind and ask questions. “Da dharmasth, we have lost the will of my grandfather. Please tell us where to find it.” And then you ask questions. “Is it in the bedroom?” You ask it three times; you have to wait in between. “Is it in the office?” And you wait again. “Is it in the this? Is it in the that?” You keep going through every place you can think of. And then strangely, suddenly the book drops.

You look at each other, you go like … I’ve done this one time. So, I know when the book dropped, I looked like, “What did I just say? I’ve been in this pattern of asking questions that I forgot what I just said.” That’s the answer. The book drops when you have the answer. “Yes, it is in that place, wherever you just said.” “Is it my brother’s house?” “Is it my sister’s house?” “Is it my uncle’s house?” “Is it my aunt’s house?” “Is it my nanny’s house?” “Is it my cousin’s house?” You’re asking all these questions because you’re exhaustively thinking through all the possibilities.

Suddenly, the book drops. And it’s a freaky thing because all three times, it has been successful. That’s what I can’t quite wrap my head around, is if you move it will drop, because you’re literally dangling there, but I can move at any second. I want to scratch my hair, I could move, but no, it drops at the right time. It’s almost like that Ouija board feeling of another hand turning the key. It’s literally turning the key. So, I embedded that ceremony in the third book, where you use this for objects. You never use this for people, anything that has agency. You’re not going to be able to find a dog or a cat with this method, because they can move. And we’re not supposed to overuse this precious tradition. So, you treated it with a lot of respect. She decides that since the thing that is missing is a wheelchair-bound woman who cannot wheel herself—in those early wheelchairs you could not wheel yourself—she decides that maybe it will work. She goes through this whole tradition and, lo and behold, she helps Captain Jim. She’s very uncomfortable with offering up this ancient, primitive tradition to the inspection of the ship’s captain and to Jim. But the pressures of the situation are such that she says, “All right, well, I have something that might just work,” and does it. But her trepidation and her discomfort echoes my own. Because I’m a modern woman, I think I believe in science; I think I understand reason and rational behaviour, and I recommend it; and so suddenly to be going back to this very strange archaic tradition, it felt strange to me, but I also find it valuable and precious. So, I put it into this book.

In book two, Diana is a modern woman, she has been sort of rejected by her family for marrying a non-Parsi and therefore, she’s not really sure that she is Zoroastrian. And then she goes through these trials and tribulations and at certain points that are very traumatic to her, it’s the prayers that she was taught as a child that come back to support her and help her to go on. And I think that retrieving her own personal faith, her own personal identity, claiming her place as a Zoroastrian mimics what a lot of us go through, because we’re born and brought up, many of us, in modern non-Zoroastrian enclaves. You grow up, all your friends are not Zoroastrian or not Parsi. Some of us are lucky enough to have communities nearby, but the vast majority of us don’t have a temple to go to or an association or may not even meet another Zoroastrian for 20 years of their life. So how do you then have a sense of identity and personal faith? I thought that this experience, hidden in there is an Easter egg.

And then there’s food. There are all these little recipes here and there. At one point, Diana’s all beat up or whatever, and there’s a custard that is brought to her and it reminds her of her mother’s custard. Then there’s akuri, which is an egg burji, like a scrambled egg with lots and lots of spices and condiments and tomatoes and onions. When I talk about them, there’s water in my mouth because they bring back such a strong emotional response and fondness for the culture of the community. These are hidden here and there. They’re part of the story. They’re not really asides, but because the characters are who they are, the traditions are reflected in their stories.

II: Yeah, I know you’re friendly with a cookbook writer, Niloufer …

NM: Niloufer Malavala. Niloufer’s Kitchen. I’ve been making it for 20 years, maybe 25 years. I attended her class, and that was one of the dishes. I tell you, every time now I go back to her recipe, because she makes it better than the way I learned and used for 20 years. Her recent book is called The Route to Parsi Cooking. And it’s not just about cooking. It’s about the Silk Road and the way that spices have evolved and the way that the berry pulao has evolved, the way that we’ve taken Persian traditions, and modified them, adopted English cooking, adopted so many different styles, and made it something different. There is a very specific taste that’s more like a sweet and sour taste that is in a lot of our patias and things. And that is very uniquely Parsi. But every dish, of course, has its own unique flavour and she’s preserved a lot of the traditional methods and the traditional ways that it should taste. If you follow her recipe, you will get an authentic end product.

II: I will. I cook Parsi food quite a lot. I’ve been using the recipe book from the London restaurant Dishoom. It’s my favourite Parsi place in London. But someone needs to open a Parsi restaurant in Sydney. Please ask her to send someone over here. There used to be one, but it has closed down and now there aren’t any.

NM: OK. An opportunity for an entrepreneur. I am going to share this talk with a number of people. I think everyone can enjoy Parsi cooking because it’s not just one thing. It’s not overly oily, overly sweet, overly spicy. Thai food tends to be a little bit on the spicy side. And I love it. But you know what you’re going to get. Here you have a blend. And I think it can be appealing to many palates. And then, of course, everybody’s hot for variety, right? Everybody wants variety. So why not discover something new? The food is indicative of this.

II: Parsis are a middleman minority, a small diaspora group who’ve often been disproportionately successful and creative and contributed a massive amount to the host culture to which they emigrated. In many places, it’s the Jews who are the middleman minority. In some places, it was the Chinese and, in India, the Parsis. There are some other middleman minorities as well in India. There’s an intrinsic celebration of kind of diversity there.

There’s a really beautiful Parsi myth, which states that when the first group of Zoroastrians arrived on the Gujarat coast, they called for the local ruler and the local ruler said, “You can’t stay here. India is full.” (Little did he know India is “chockers,” as we would say here in Australia.) “You have to go home.” And the head priest asked him to bring a large clay vessel full of milk and he called for some jaggery—palm sugar—and he put the sugar into the milk and he mixed it with a spoon and the sugar dissolved and he said, “We will live among you like the sugar in this milk, following your traditions, wearing your dress, speaking your language, having our weddings after sundown (which is the Hindu way) as long as we can continue to follow our religion. That’s almost certainly just a myth, but it’s a very beautiful myth.

I was thinking about the way in which your novels also have multiple examples of migrations, and hybrid identities, mixings and minglings. And I was reminded of this passage. This is Salman Rushdie talking about The Satanic Verses, and I think it’s apt here.

Those who oppose the novel most vociferously today are of the opinion that intermingling with a different culture will inevitably weaken and ruin their own. I am of the opposite opinion. The Satanic Verses celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the transformation that comes of new and unexpected combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas, politics, movies, songs. It rejoices in mongrelisation and fears the absolutism of the Pure. Melange, hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that is how newness enters the world. It is the great possibility that mass migration gives the world… The Satanic Verses is for change-by-fusion, change-by-conjoining. It is a love song to our mongrel selves.

I think about that passage a lot.

NM: Lovely. That is lovely and so authentic. You know, Brits do prize their bloodline. In the 1800s, Brits basically prized their bloodline because they wanted to be descended from William the Conqueror or something. You had these noble houses and so on. But recent DNA tests show that most of us have at least a quarter of Indian DNA. It’s not a hundred percent Persian, at max maybe sixty, seventy percent, if you’re lucky. But it’s not going to be a hundred percent. So, there’s no way that we were only intermarrying [intra-marrying], for all those hundreds and hundreds of years. We definitely have been intermarrying within the Indian community and others. It’s just some fear, essentially, that had closed down those borders or made that rule much more restrictive in the 1800s.

As I researched, I realised what it was. There was a time, a single year, when five young men converted to Christianity. These elders got so panicked that this sexy new religion is coming and stealing our children, that they shut the door and they said, “Neither boys nor girls shall marry outside the community. If you do you’re not going to get a job, you’re going to be shunned.” So that was a reaction, it was not the original stance. That’s how you end up with 25 percent DNA from mingling with other races and you still have this aura of, “Oh we are all so pure because we only ever intermarried within ourselves.” It’s a total myth.

II: Yeah. I think it would be nice to finish with one more passage from the book. Would you like to read one or shall I?

NM: Oh, go ahead. I have not picked one.

II: OK. In that case, I will. I’m sorry to take over so much of the reading.

NM: No, I love it! You read so well!

II: Thank you. So, this passage will give you a sense of the sort of swashbuckling excitement which is very frequent in your novels. And it’s set up in modern day Pakistan at this point, in what is now northwest frontier Pakistan, on the border with Afghanistan. I think you don’t need more context than that. I’m just going to read the passage.

Ranbir said he’d avoided several Afghan soldiers, then grinned. “These people are very superstitious! That old palace by the river, in the broken fort? They are all afraid of it. They say the zenana, the women’s quarters, is haunted.”

“Haunted? Why?” I ate a kebab, wondering what use this knowledge might be.

“An old shoemaker told me the story. Some two hundred years ago a Moghul king tried to capture Pathankot. This town was the stronghold of a Pathan Thakur and his queen the Thakurani.” Ranbir mused, “There are many such tales in these mountains.”

“Why is it haunted?” I dunked the last kebab into an earthen pot of yogurt and popped it into my mouth.

“The Thakur died bravely in battle. But the Thakurani would not be taken. Rather than become slaves, she and all her court ladies committed Johur. They jumped from the battlements and died.”

A shiver ran down my arms. It sounded strangely like the mystery I needed to unravel. Two centuries later, had Lady Bacha and Miss Pilloo faced a similar threat?

“The old man said their ghosts cry out still.” Ranbir continued, “Their wails are heard on quiet nights.”

Sceptical, I frowned. “From the zenana?”

Dusk was upon us as we decided to search the crumbling fortifications on the edge of town. The Gurkha troop might have secured themselves in its maze of corridors and tunnels, but in the dark, how could we find them?

Ranbir paid the sleepy stableman, who spat sideways on the straw and then untied our horses. I climbed into the saddle and pointed my Arabian to the town outskirts. She walked gently, hooves clip-clopping in the starry night. The market having closed, we wove through a few villagers trudging homeward.

Night comes quickly in the mountains. The air was crisp and still. Navigating cobbles, long since crumbled, that lay loose and uneven in our path, our horses’ hooves clinked on stone, high notes interspersed with hoofbeats. I winced—could the sentries at the crossroads hear us?

The fortress loomed, dark and formless. It had been shelled years ago, leaving wide gashes in the wall, a wall that bled piles of stone, great blocks of it slowing our pace.

The outer fortifications towered on my right. I nudged my horse along the perimeter, trusting her to navigate the rubble. Reins slack, she stepped carefully, dropping her head now and again to sniff at stones. Stopping at a dark hollow, a crevice in the wall, she shook her mane as though to ask, “Are you bloody sure you want to do this?”

She’d found the way into the fortress, but could we find our way out?

Night is not the time to explore unfamiliar terrain, yet it was all we had—my injury had cost us three days. With a nudge of my knees, the Arabian stepped through the broken archway into the fortress courtyard.

A sliver of moon left the clouds to gleam high above, allowing me a view of vast fortifications. Two turrets loomed at either end of a forward wall, vantage points to pick us off with a bullet. The courtyard offered no shelter between outer and inner walls, a space designed to trap intruders.

“Bao-di,” said Ranbir, “this is not a good place.”

An archway to one side led to an inner locus, the zenana or women’s quarters, marked by narrow windows overlooking a courtyard. I hesitated, reluctant to enter a maze of unfamiliar passages, but there was no help for it. We must find Greer’s men and Doctor Aziz. Grateful for moonlight, I searched the shadows for movement. The air was cooler amid the fog and silent stones. Among these walls, one could almost believe in spirits.

Suddenly a plaintive wail wound through the ruin, creeping over bare stones, chilling in its despair. My breath caught, disbelieving. The Arabian lurched sideways, hooves clattering, a familiar sound, comforting in its normalcy, in contrast to the otherworldly cry.

The screech faded, leaving an expectant silence. I held tight to the reins, cold creeping over my skin. We should leave this alien place.

“What is it?” Ranbir whispered. My hands soothing my mount, rubbing her twitching withers, I said, “Steady, old girl.”

There was something peculiar about the torn cry, a familiar quality, despite its eerie resonance. When I nudged the Arabian, she set off at a happy trot. Astonished, I held her back, until I realized that her gait meant something. Could she know that sound?

Then it struck me. Good Lord—that eerie note came from army bagpipes!

I loosed the reins, letting the Arabian find it. Ranbir followed, uttering prayers.

The Arabian sidled to a stairway, her feet dancing, her ears up and alert, eager and high-strung. I dismounted, holding her bridle.

“Rookoh!” A voice commanded me to stop.

I stiffened, heard Ranbir’s startled breath and understood. The Sepoys of the Twenty-first Gurkha Rifle Regiment were expert snipers. Only their reluctance to reveal themselves had saved us from a marksman’s bullet.

Still clinging to the saddle, I whistled two notes every Sepoy would know.

Someone chuckled. “Mess call,” the quiet voice said in English.

We had found the troop. I felt giddy with relief. “Righto. Can you play ‘Loch Lomond’ on those pipes?”

A short Gurkha in khaki uniform stepped out of the shadows a few feet away, smiling. I admit to a warm rush of relief, even ebullience, then. The troop had survived in the fortress for weeks and surely knew every turn of these blasted passages. Their ruse, those ghostly wails, kept away enemy soldiers and townsfolk by night. With their help we might escape this place.”

OK, that’s it.

NM: Lovely! Thank you, Iona!

II: Thank you so much for joining me. I would highly recommend the novels. They are very fun, light, easy page-turners, but they’ve also got, as you might be able to tell, quite a literary quality. The description is very lush and they are really thoroughly historically researched. Just great storytelling.

NM: Thank you so much. I love hearing from readers, so if you read it and you enjoyed one of the books, write to me at nevmarch.com.

II: Brilliant. Thank you so much. Thank you for listening everyone.